Tag: Women

10

Nov 2011

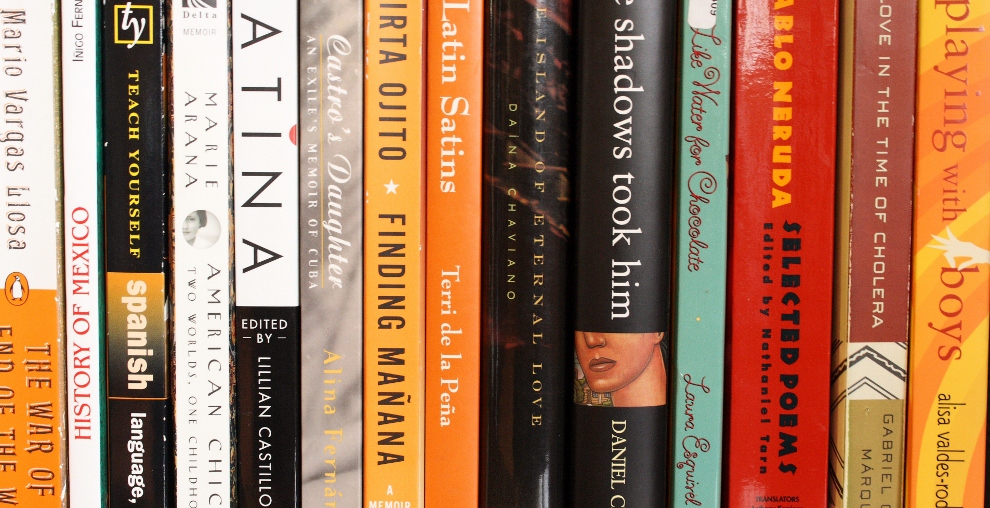

Latina Self-Portraits and Helena Maria Viramontes

posted in: Authors, books, Helena Maria ViramontesSometimes I sit down to write and think, What do I write about? What interesting thing has happened to me that qualifies me to write a piece that is lucid on the topic of human nature? What can I say, it’s a writer’s neurosis. When I read works by Latina authors, I find myself relating to them, nodding my head and thinking, “Exactly!” and, “How did they know that?” It is then that I realize that writing what you know is hard because it’s actually writing everything that you take for granted.

Latina Self-Portraits, edited by Bridget Kevane and Juanita Herdia, is a somewhat older book (published in 2000 by University of New Mexico Press) that contains the interviews of 10 Latina authors, including Cherríe Moraga, Sandra Cisneros, and Julia Alvarez. The introduction is a bit scholarly (I actually think I bought this for a college project on Chicano literature), but the interviews are frank and interesting, so it really doesn’t matter whether your aim is to “[define] the literary space of Latina literature” or if you’re just interested in hearing what the authors had to say. I was astounded that even though the interviews took place in the late 1990s, the author’s thoughts and commentary on Latino culture are still so relevant. I did have to chuckle when Julia Alvarez, asked about a younger generation of Latino writers, says, “Oh yeah! Junot Díaz!”

Anyway, I was looking back over this book which I read a few years ago and wanted to focus on an author whose work I haven’t read. I picked Helena Maria Viramontes. Viramontes is the author of The Moths and Other Stories, Under the Feet of Jesus, and Their Dogs Came with Them.

The interview touches on several topics from farmworkers to her personal life to the influence of corridos. I LOVE that Viramontes says that the answer to whether to italicize phrases in Spanish is “absolutely not.” I feel the same way, at least for Latino literature. To me, Spanish is not a foreign language in our culture, so I don’t think the style rule applies.

Viramontes also talked about the writing process. Of the solitude of writers, she said, “We arrive in our seats with our sense of insecurities as human beings incapable of capturing the visions in our heads. With our open bleeding hearts, we arrive to make some understanding for ourselves and for the readers.”

One of Viramontes’s well-known short stories is “The Moths,” about a girl and her dying grandmother. The haunting story was inspired by an equally haunting photograph of a Japanese woman bathing her deformed child.

Viramontes writes a story of a girl caught between two cultures. The details are true. I can’t think of a better word, they’re just TRUE. The main character at one point remembers, “As I opened the door and stuck my head in, I would catch the gagging scent of toasting chile on the placa. . . . The chiles made my eyes water.”

Just yesterday I opened the window while toasting chiles on the placa, and wondered to myself why I don’t just roast them in the oven like I see gringos doing on television. Maybe it wouldn’t burn so much. But no, that wouldn’t be like my abuela did. And that simple part of making dinner made me remember my abuela and her housekeeping, her embroidery and tejidos, and sus hierbas for curing all ills. Today I read about my grandma in Viramontes’s story.

I won’t reveal more details because it would spoil such a short story. You have to read it yourself. But I think that this is the greatest compliment I can give an author – that when I read this story, I saw myself.

no comments3

Nov 2011

A Radical Blogger Profile

posted in: blogsUh, what’s a doula?

At the end of my pregnancy, I met a doula who specialized in supporting immigrant non-English speaking women. I didn’t really know what a doula was or how having a stranger at my delivery fit in to the big picture, so I didn’t follow up. I later read about Miriam Zoila Pérez, another doula, in Latina magazine. I figured it was time to look into this.

Pérez blogs at radicaldoula.com. She describes a doula as “the one person who’s not worried about anything else that’s going on,” someone who provides emotional and psychological support to a mother during childbirth.

After deciding that pre-med wasn’t for her, and seeing the natural birth documentary The Business of Being Born, Pérez decided to become a midwife, but was advised to become a doula because she wanted to work with lesbian and immigrant women. She spent a semester in Ecuador and volunteering in a maternity ward (not as an official doula). After returning to the States, Pérez trained to become a doula, working mostly with Latina immigrants.

Working with Immigrants

While working with immigrants, Pérez saw a discrepancy between the quality of care for Latina immigrants versus insured white women. One of the biggest issues was the language barrier. The hospital where Pérez worked only brought in an interpreter when papers are to be signed. The doctors “chose what they wanted to communicate and spoke English otherwise . . . imagine – what does that do to your quality of care?”A doula is not a translator, but Pérez was still challenged on how much to communicate to the mother.

According to Pérez, most Latinas give birth in a hospital instead of choosing natural birth at home or in a birthing center. She attributes this to the fact that in Latin America there is a “big push” by the World Health Organization and other developmental organizations for women to give birth in hospitals, because they see it as “a marker of development.” Immigrants also choose hospitals as a sign of class and social status – “in Latin America you go to the hospital if you can afford it,” Perez says.

When it comes to second and third generation Latinas, their positions on childbirth tend to come more in line with the general American population.

Full-Spectrum Doulas

Giving birth is not the only life-altering event in a woman’s reproductive health. Women also face abortions, miscarriages, and other events. This is where full-spectrum doulas such as Pérez come into play. A full-spectrum doula supports a woman not only during birth but for abortion, adoption, surrogacy and miscarriage.

Supporting women during abortions (some of these procedures are actually to help a woman who had a partial miscarriage) is quite controversial in the doula community. “I felt like I wasn’t connecting in the doula community] and wanted to talk about why being pro-choice made sense to me,” Perez says. She started the blog – a “new arena” at the time – to build the connections she sought.

Blogging/Feministing/Activisting

Perez has expanded from being a doula to blogging about it to writing, editing at feministing.com, and activism. She is a consultant for The National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health. She also has been nominated her for the 2011 Women’s Media Center Social Media Award! If you go to the Women’s Media Center website, you can scroll over to read about her nomination and then vote for her to win!

Punto

Having a baby is a beautiful and disgusting, exhausting and exhilarating, joyous and terrifying. Everyone gives you their crazy advice and horror stories. As a Latina, others might not understand your culture and family dynamics.

Even if you have a supportive husband and family visiting during labor, you wish they would get the hell out of the way during the trying moments of labor – but at the same time, you want someone to be there with you. This person could be a doula.

Latinas have diverse backgrounds and individual experiences with chilbirth, and our cultura should be taken into account to provide a supportive atmosphere during childbirth.

Other reproductive issues are often fraught with the same conflicting emotions. Thanks to doulas/bloggers/activists like Miriam Perez, we know that there is someone out there that can provide support to us during those tough times.

1 comment